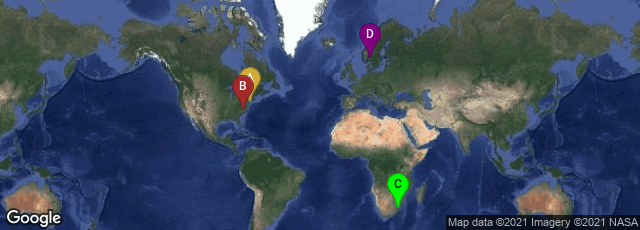

A: Brooklyn, New York, United States, B: Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States, C: KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, D: Nordre Aker, Oslo, Oslo, Norway

On March 1, 2014 Claudia Funke, Curator of Rare Books at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, drew my attention to a non-written Zulu beadwork love letter preserved in the "Curosities Cabinet" at the UNC rare book collection. Zulu, the language of about 10 million people, 95% of whom live in South Africa, was not a written language until contact with missionaries from Europe, who documented the language using Latin script. The first grammar book of the Zulu language was published in Norway, rather than in South Africa, by the Norwegian missionary Hans Schreuder, founder of the first Christian mission in Zululand: Grammatike for Zulu-sproget, forfattet af H.P.S. Schreuder (Christiania [Oslo], 1850). According to the Wikipedia, the first published book printed in Zulu was a Bible translation: Ibaible eli ingcwele; eli Netestamente Elidala, Nelitya, kukitywa kuzo izilimi zokuqala, ku lotywa ngokwesizulu. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments, translated out of the original tongues, into the Zulu language (New York: American Bible Society, 1883). Considering how late reading and writing came to the Zulus, we can well understand how non-written communication evolved in this culture in interesting ways.

According to Claudia Funke,

"In 1937, Daniel M. Malcolm, Chief Inspector of Native Education in Natal, South Africa, brought the letter to UNC-Chapel Hill as a visual aid for a lecture he gave at that year’s “Conference on Education of American Negroes and African Natives.” Malcolm explained that the letter was written by a girl to her beloved. The white beads indicate the purity of her heart, and the red beads show that her heart is broken and bleeding for her beloved. The four black squares represent four questions about their relationship that he must answer. Malcolm gave the love letter to UNC and its Hanes Foundation for the Study of the Origin and Development of the Book. It subsequently became part of the RBC’s “Curiosities Cabinet,” which houses many other non-codex objects of significance for the history of the book, such as cuneiform tablets and papyrus fragments."

It may be impossible to date the Zulu beadwork love letter at UNC accurately, so I assigned the accession date at UNC as a terminal date for this entry.

Long after Zulus achieved literacy, the tradition of non-written, or at least partly non-written, Zulu love letters appears to be continuing, as reflected in the 2004 film Zulu Love Letter: