Engraving of Sir Robert Peel, 1st Baronet, by John Henry Robinson (mid 19th century)

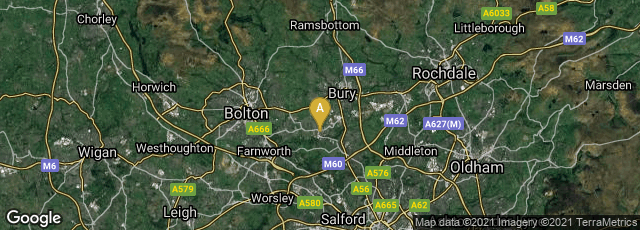

A: Radcliffe, Manchester, England, United Kingdom

After the passage of the Apprentice Act, in June 1802 textile manufacturer and politician Sir Robert Peel (father of the Prime Minister) wrote to a colleague requesting his assistance in placing printed posters of the text of the act in mills and factories, so that managers and operators of the factories could not plead ignorance of the law once it came into effect in December 1802. This law, which was formally known as the "Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802," was the first of a very long series of legislative reforms of factory labor that continued in Great Britain up to the present. It was not extensively enforced. Peel's undated autograph letter, which presumably was written around November, 1802, reads as follows:

"Dear Sir

"If I recollect right you had an intention to publish some copies of the Apprentice Act on large paper to be sold cheap for the use of mills by Booksellers in Manchester Derby, Glasgow, Dublin & c. and as the time draws near for the act to operate the sooner this is done the better. Your laudable intentions will not be answered unless the regulations are generally adopted and if such a measure is taken speedily no excuse can be pleaded of inability to comply with the act. I rather think I shall attend my duty in Pariliament before Christmas and hope to have the pleasure of seeing you on my reaching town. Lady Peel unites with me in best regards to Bernard & your self, Dear Sir, Robert Peel

"PS. The Act should be on one sheet to be placed against a wall, door & c."

"During the early Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom, cotton mills were water-powered, and therefore sprang up where water power was available. When, as was often the case, there was no ready source of labour in the neighbourhood, the workforce had to be imported. A cheap and importable source of labour was 'parish apprentices' (pauper children, whose parish was supposed to see them trained to a trade or occupation ); millowners would reach agreement with distant parishes to employ, house and feed their apprentices. In 1800 there were 20,000 apprentices working in cotton mills,.[1] The apprentices were vulnerable to maltreatment by bad masters, to industrial accidents, to ill-health from their work, ill-health from overwork, and ill-health from contagious diseases such as smallpox, typhoid and typhus, which were then widespread.[2] The enclosed conditions (to reduce the frequency of thread breakage, cotton mills were usually very warm and as draught-free as possible) and close contact within mills and factories allowed contagious diseases such as typhus and smallpox to spread rapidly. Typhoid (like cholera, which did not reach Europe until after the Napoleonic wars) is spread not by poor working conditions but by poor sanitation, but sanitation in mills and the settlements round them often was poor.

In about 1780 a water-powered cotton mill was built for Robert Peel on the River Irwell near Radcliffe; the mill employed child labour bought from workhouses in Birmingham and London. Children were unpaid and bound apprentice until they were 21. They boarded on an upper floor of the building, and were locked in. Shifts were typically 10–10.5 hours in length (i.e. 12 hours after allowing for meal breaks), and the apprentices 'hot bunked' : a child who had just finished his shift would sleep in a bed only just vacated by a child now just starting his shift. Peel himself admitted that conditions at the mill were "very bad".[3]"

"Each apprentice was to be given two sets of clothing, suitable linen, stockings, hats, and shoes, and a new set each year thereafter. Working hours were limited to 12 hours a day, excluding the time taken for breaks. Apprentices were no longer permitted to work during the night (between 9 pm and 6 am).[10] A grace period was provided to allow factories time to adjust, but all night-time working by apprentices was to be discontinued by June 1804.[7]

"All apprentices were to be educated in reading, writing and arithmetic for the first four years of their apprenticeship. The Act specified that this should be done every working day within usual working hours but did not state how much time should be set aside for it. Educational classes should be held in a part of the mill or factory designed for the purpose. Every Sunday, for one hour, apprentices were to be taught the Christian religion; every other Sunday, a divine service should be held in the factory, and every month the apprentices should visit a church. They should be prepared for confirmation in the Church of England between the ages of 14 and 18 and must be examined by a clergyman at least once a year. Male and female apprentices were to sleep separately and not more than two per bed.[10]

"Local magistrates had to appoint two inspectors known as visitors to ensure that factories and mills were complying with the Act; one was to be a clergyman and the other a Justice of the Peace, neither to have any connection with the mill or factory. The visitors had the power to impose fines for non-compliance and the authority to visit at any time of the day to inspect the premises.[10]

"The Act was to be displayed in two places in the factory. Owners who refused to comply with any part of the Act could be fined between £2 and £5.[c][10]" (Wikipedia article on Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, accessed 11-23-2018).