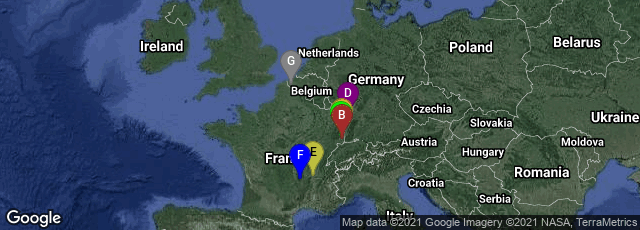

A: Colmar, Grand Est, France, B: Mulhouse, Grand Est, France, C: Rouffach, Grand Est, France, D: Wissembourg, Grand Est, France, E: Vienne, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France, F: La Chaise-Dieu, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France, G: Ieper, Vlaanderen, Belgium

in this miniature from a manuscript Speculum. Eleazar Maccabeus kills the elephant and is crushed. Lyon - BM-ms. 0245 -F.144.

The Speculum humanae salvationis or Mirror of Human Salvation, a bestselling anonymous illustrated encyclopedic work of popular theology, originated between 1309 (since it refers to the Pope being at Avignon) and 1324, the date on two copies. A preface, probably from the original manuscript, states that the author did not identify himself out of humility, though numerous suggestions of authorship have been made. The author was almost certainly a cleric, and there is evidence he was a Dominican. A leading candidate for authorship is Ludolph of Saxony; Vincent of Beauvais has also been proposed.

The Speculum humanae salvationis falls into the category of encyclopedic speculum literature concentrating on the medieval theory of typology, in which events of the Old Testament foretold events of the New Testament. The original version was in rhyming Latin verse, describing a series of New Testament events, each of which was prefigured by three Old Testament events. The work must have been very widely copied, as it remains one of the most widely preserved of illuminated manuscript texts; over 350 medieval manuscript copies survive in Latin, and the text was also translated and copied into Dutch, French, German, English and Czech. Almost all the copies were illustrated, following the pattern of the manuscripts dated 1324, but from an exemplar that was probably lost. "In the prologue is the statement that the learned can find information from the scriptures, but the unlearned must be taught by pictures, which are the books of the lay people" (Wilson & Wilson 24). It was also one of the most widely printed texts in the fifteenth century, both in blockbook and editions printed from movable type. There were four blockbook editions (two in Latin and two in Dutch), and sixteen editions printed from movable type by 1500.

"No works of the late Gothic had more influence on artists working in all the media than the Biblia pauperum and the Speculum humanae salvationis. The influence of the typological text and illustrations of the latter can be seen in the fourteenth-century stained glass windows of churches at Mulhouse, Colmar, Rouffach, and Wissembourg. The woodcuts of the blockbooks clearly appear in designs of the fifteenth-century sculptures of the church of Saint-Maurice at Vienne and in the famous tapestries of the Life of Christ at La Chaise-Dieu and the series at Rheims. Mâle states that one could be sure that any Flemish artist of importance had in his atelier manuscripts of these two works. Jan van Eyck, in 1440, worked from a Speculum in the triptych for the church of Saint-Martin in Ypres. The typological treatment of the Nativity was traditional and one might assume that Van Eyck could find it in other sources, but on the exterior of the side panel is the earliest example, in panel painting, of the Annunciation to Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl just as it appears in the Speculum. This subject entered the artistic iconography specifically through the Speculum text and image. There was a copy also in the atelier of Roger van der Weyden, as can be seen in the famous Bladelin triptych, where the same prefigurations of the Nativity are pictured. The use of both books as sources, in a single work of art, is not uncommon" (Wilson & Wilson, A Medieval Mirror. Speculum humanae salvationis 1324-1500 [1984] 28-29).

In November 2013 a digital facsimile of an illuminated manuscript of the Speculum humanae salvationis produced in Paris or Flanders circa 1430-1450 and preserved in Einsiedeln at the Stiftsbibliothek was available from e-codices at this link. Another digital facsimile of an illuminated manuscript, preserved in Sarnen at the Benediktinenkollegium, written in 1427, possibly by Brother Thomas de Austria ordinis sancti Johannis, was available from e-codices at this link.

As of 2018, the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database included "complete sets of illustrations of about 50 manuscripts and 10 manuscript fragments as well as incomplete sets of over 25 manuscripts, and furthermore all woodcuts used in printed editions. This documents about one third of the extant illustrations of the Speculum, and it contains examples from Italy, Germany, Hungary, Bohemia, England, the Netherlands and France from the early 14th to the end of the 15th century, from masterpieces to rough outline drawings."