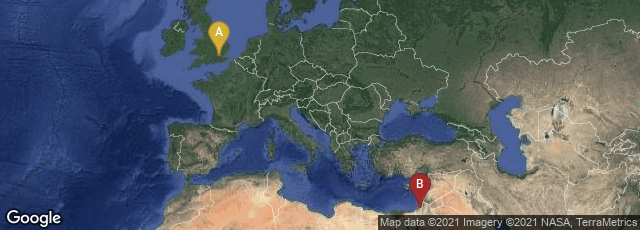

A: London, England, United Kingdom, B: Jerusalem, Jerusalem District, Israel

More than one million charters survive, either as originals or early copies, from the period of Norman rule in Britain, from 1066 to 1307. Many of these documents are records of property and land transactions written in Latin and recorded by religious or royal institutions. They are fundamental source material for historical research in medieval politics, economics and society.

Through these charters historians can study the rise and fall of military and religious organizations, among many other topics. For example, charters show how the Knights Hospitallers, or the Order of Saint John, a religious organization founded around 1023 to provide care for poor, sick or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land, became a religious and military organization after the Western Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade, when it was charged with the care and defense of the Holy Land.

In the late seventeeth and early eighteenth centuries dating medieval charters was one of the problems which motivated Mabillon and Montfaucon to pioneer the science of palaeography. However, at least one million of the Norman charters remain undated, largely due to adminstrative changes introduced by William the Conqueror in 1066. To solve problem of dating the huge number of undated charters Gelila Tilahun and colleagues at the University of Toronto are applying computer-automated statistical techniques with the goal of reducing the time and effort to date them manually, and to improve the accuracy of assigned dates.

"Their approach is to use a subset of some 10,000 charters that are dated and to look for changes in language over time that could be used to date other documents. For example, Tilahun and co say that the phrase “amicorum meorum vivorum et mortuorum”, which means 'of my friends living and dead', was popular between the years 1150 and 1240 but not at other times. And the phrase 'Francis et Anglicis', which is a form of address meaning 'to French and English', was phased out when England lost Normandy to the French in 1204. However, the statistical approach is much more rigorous than simply looking for common phrases. Tilahun and co’s computer search looks for patterns in the distribution of words occurring once, twice, three times and so on. 'Our goal is to develop algorithms to help automate the process of estimating the dates of undated charters through purely computational means,' they say.

"This approach reveals various patterns which they then test by attempting to date individual documents in this set. They say the best approach is one known as the maximum prevalence technique. This is a statistical technique that gives a most probable date by comparing the set of words in the document with the distribution in the training set.

"Tilahun and co say their approach also has other applications. For example, the same technique could be used to work out authorship and to weed out forgeries, of which there are known to be a substantial number.

"So how well does it work in practice? These guys finish their paper with a fascinating anecdote about a medieval English charter that was discovered in a drawer at the library of Brock University near Niagara Falls. T

"The charter lacked a data so various historians attempted to work out when it was written. The first estimates pointed to the 14th century but these were later revised to the 13th century. Eventually, by comparing the charter to other records, one academic pinned it down to a date between 1235 and 1245.

"Inspired by the media interest in this charter, Tilahun and co ran the document through their automated maximum prevalence procedure. 'The date estimate we obtained was 1246,' they say, with just a little hint of pride. Not bad!" (MIT Technology Review, 01-16-2013, accessed 01-16-2013).

Gelila Tilahun, Andrey Feuerverger, and Michael Gervers, "Dating medieval English charters," Annals of Applied Statistics VI (2012) 1615-1640.