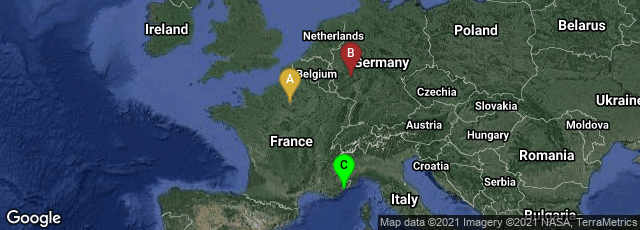

A: Paris, Île-de-France, France, B: Bad Ems, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany, C: Cagnes-sur-Mer, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France

In 1930 prolific American avant-garde writer Bob Brown (Robert Carlton Brown), published an essay entitled "The Readies" in the international avant-garde journal transition, issued from Paris, no. 19/20, 167-73, calling for a new reading machine, and new reading material for it called "The Readies." Brown intended these innovations as ways for literature to keep up with the advanced reading practices of a cinema-viewing public, as epitomized in the then new expression for sound films, "the talkies." The first feature film originally presented as a talkie had been The Jazz Singer, released in October 1927.

"The word 'readies' suggests to me a moving type spectacle, reading at the speed rate of the day with the aid of a machine, a method of enjoying literature in a manner as up-to-date as the lively talkies. In selecting the "The Readies' as title for what I have to say about modern reading and writing I hope to catch the reader in a receptive progressive mood. I ask him to forget for the moment the existing medievalism of the BOOK (God bless it, it's staggering on its last leg and about to fall) as a conveyer of reading matter. I request the reader to fix his mental eye for a moment on the ever-present future and contemplate a reading machine which will revitalize this interest in the Optical Art of Writing.

"In our aeroplane age radio is rushing in television, tomorrow it will be commonplace. All the arts are having their faces lifted, painting (the moderns), sculpture (Brancusi), music (Antheil), architecture (zoning law), drama (Strange Interlude), dancing (just look around you tonight), writing (Joyce, Stein, Cummings, Hemingway, transition). Only the reading half of Literature lags behind, stays old-fashioned, frumpish, beskirted. Present-day reading methods are as cumbersone as they were in the time of Caxton and Jimmy-the-Ink. Though we have advanced from Gutenberg's movable type through the linotype and monotype to photo-composing we still consult the book in its original form as the only oracular means we know for carrying the word mystically to the eye. Writing as been bottled up in books since the start. It is time to pull out the stopper.

"To continue reading at today's speed I must have a machine. A simple reading machine which I can carry or move around and attach to any old electric light plug and read hundred thousand word novels in ten minutes if I want to, and I want to. A machine as handy as a portable phonograph, typewriter or radio, compact, minute operated by electricity, the printing done microscopically by the new photographic process on a transparent tough tissue roll which carries the contents of a book and is no bigger than a typewriter ribbon, a roll like a minature serpentine that can be put in a pill box. This reading film unrolls beneath a narrow magnifying glass four or five inches long set in a reading slit, the glass brings up the otherwise unreadable type to comfortable reading size, and the reader is rid at last of the cumbersome book, the inconvenience of holding its bulk, turning its pages, keeping them clean, jiggling hs weary eyes back and forth in the awkward pursuit of words from the upper left hand corner to the lower right, all over the vast confusing reading surface of a page....

"My machine is equipped with controls so the reading record can be turned back or shot ahead, a chapter read or the happy ending anticipated. The magnifying glass is so set that it can be moved nearer to or father from the type, so the reader may browse in 6 points, 8, 10, 12, 16 or any size that suits him. Many books remain unread today owing to the unsuitable size of type in which they are printed. A number of readers cannot stand the strain of small type and other intellectual prowlers are offended by Great Primer. The reading machine allows free choice in type-point, it is not a fixed arbitrary bound object but an adaptable carrier of flexible, flowing reading matter....

"The machine is equipped with all modern improvements. By pressing a button the roll slows down so an interesting part can be read lesurely, over and over again if need be, or by speeding up, a dozen books can skimmed through in an afternoon without soiling the fingers or losing a dust wrapper....

"The material advantages of my reading machine are obvious, paper saving by condensation and elimination of waste margin space which alone takes up a fifth or sixth of the bulk of the present-day book. Ink saving in proportion, a much smaller surface needs to be covered. . . Binding will be unnecessary, paper pill boxes are produced at the fraction of the cost of cloth cases. Manual labor will be minimized. Reading will be cheap and independent of advertising which today carries the cost of the cheap reading matter purveyed exclusively in the interests of the advertiser" (167-69).

Brown also intended his device as one way of achieving "The Revolution of the Word," as called for in the manifesto published in issue 16/17 of transition by its editor Eugene Jolas in 1929. Later in 1930 Brown privately published a 52-page pamphlet entitled The Readies in an edition of 150 or 300 copies. The imprint of the pamphlet read Bad Ems: Roving Eye Press. (It is possible that the publishing location was a joke.) The pamphlet represented an expansion with examples given, of Brown's essay from transition, a revised version of which it republished as chapter 3.

Written before anyone imagined electronic computers, and even longer before anyone imagined a hand-held electronic computer, one goal of Brown's vision of new media for reading was saving space, paper and ink through media more compact than traditional printed books. Though he could not foresee how the changes would actually occur, he was also an extremely early predictor of changes to the traditional codex book that would occur sixty years later with electronic publishing. In the pre-electronic computer era Brown, like Emanuel Goldberg and Vannevar Bush, saw the future of of information primarily in the context of film and microfilm, and in developing more verbally compact means of communication. While Goldberg and Bush were focussed on developing more efficient means of information storage and retrieval, Brown was focussed on the creative aspects of new writing and new forms of communication with the reader:

"This important manifesto, on a par with André Breton's Surrealist manifestos or Tristan Tzara's Dadaist declarations, includes plans for an electric reading machine and strategies for preparing the eye for mechanized reading. There are instructions for preparing texts as “readies” and detailed quantitative explanations about the invention and mechanisms involved in this peculiar machine.

"In the generic spirit of avant-garde manifestos, Brown writes with enthusiastic hyperbole about the machine's breathtaking potential to change how we read and learn. In 1930, the beaming out of printed text over radio waves or in televised images had a science fiction quality—or, for the avant-garde, a fanciful art-stunt feel. Today, Brown’s research on reading seems remarkably prescient in light of text-messaging (with its abbreviated language), electronic text readers, and even online books like the digital edition of this volume. Brown's practical plans for his reading machine, and his descriptions of its meaning and implications for reading in general, were at least fifty years ahead of their time....

"Brown’s reading machine was designed to 'unroll a televistic readie film' in the style of modernist experiments; the design also followed the changes in reading practices during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Gertrude Stein understood that Brown’s machine, as well as his processed texts for it, suggested a shift toward a different way to comprehend texts. That is, the mechanism of this book, a type of book explicitly built to resemble reading mechanisms like ticker-tape machines rather than a codex, produced—at least for Stein—specific changes in reading practices.

"In Brown’s Readie, punctuation marks become visual analogies. For movement we see em-dashes (—) that also, by definition, indicate that the sentence was interrupted or cut short. These created a 'cinemovietone' shorthand system. The old uses of punctuation, such as employment of periods to mark the end of a sentence, disappear. Reading machine-mediated text becomes more like watching a continuous series of flickering frames become a movie" (Afterward from: The Readies, edited with an Afterward by Craig Saper, Houston: Rice University Press, [2009], accessed 05-23-2010).

After Brown published The Readies authors in the transition circle sent him pieces intended for publication on the hypothetical machine. In 1931 he self-published these as a 208-page book, Readies for Bob Brown's Machine, in an edition of 300 copies also from the Roving Eye Press, but this time from Cagnes-sur-mer. That work, which contained contributions by 42 authors including Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, and Paul Bowle's first appearance in a book, contained two crude illustrations of a prototype of Brown's reading machine — a wooden contraption that hardly embodied machine-age sleekness; part of it looked a bit like a waffle iron. It is unclear whether Brown's machine ever operated; probably it did not. What matters more are Brown's futuristic ideas.

——————

♦ Following the "all digital" policy of Rice University Press since it was re-organized in 2006, the Rice edition of The Readies was available as a free download from their website, or as print-on-demand from QOOP.com. When I clicked on the purchase button on 05-23-2010, I was given the following purchase options at QOOP.com:

"+Hard Bound Laminate for $25.85

"+Hard Bound - Dust Jacket for $32.35

"+Wire-O for $16.00

"+eBook for $7.00."

♦ When I attempted to access QOOP.com in June 2013 it appeared that the site had closed down. An electronic version of Bob Brown's The Readies was then freely available at Connexions (cnx.org).