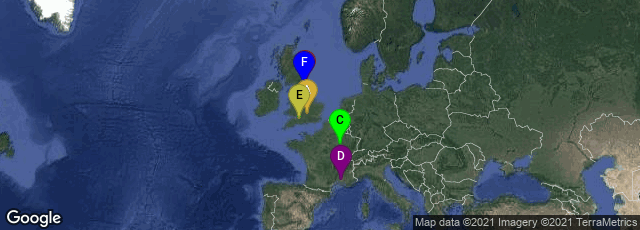

A: Oxford, England, United Kingdom, B: Durham, England, United Kingdom, C: Brienne-le-Château, Grand Est, France, D: Avignon, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, France, E: Wells, England, United Kingdom, F: Bishop Auckland, England, United Kingdom

Shortly before his death in 1345, the priest, bishop, politician, diplomat and bibliophile Richard Aungerville, commonly known as Richard de Bury, wrote Philobiblon, perhaps the earliest treatise on the value of preserving neglected or decaying manuscripts, on building a library, and on book collecting. de Bury was appointed tutor to the future King Edward III while Edward was Prince of Wales, and, according to Thomas Frognall Dibdin, inspired the prince with his own love of books.

Having connections in the court, de Bury somehow became involved in the intrigues preceding the deposition of King Edward II, and in 1325 supplied Queen Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer, in Paris with money from the revenues of Brienne, of which province he was treasurer. For a period of time he had to hide in Paris from the officers sent by Edward II to apprehend him.

Upon his ascent to the throne in 1327 Edward III rapidly promoted de Bury, appointing him cofferer to the king, treasurer of the wardrobe and afterwards in 1329 Lord Privy Seal. The king repeatedly recommended him to the pope, and twice sent him, in 1330 and 1333, as ambassador to the papal court in exile at Avignon. On the first of these visits Richard met a fellow bibliophile, Petrarch, who recorded his impression of Aungerville as "not ignorant of literature and from his youth up curious beyond belief of hidden things." Pope John XXII made de Bury his principal chaplain, and presented him with a rochet in earnest of the next vacant bishopric in England.

During his absence from England in February 1333 de Bury was appointed Dean of Wells. In September of the same year, he was appointed Bishop of Durham by the king. In February 1334 de Bury was made Lord Treasurer, an appointment he exchanged later in the year for that of Lord Chancellor. Richard may have sometimes exploited his political power to collect manuscripts. According to the Wikipedia, an abbot of St Albans bribed him with four valuable books, and de Bury, who procured certain coveted privileges for the monastery, bought from him thirty-two other books for fifty pieces of silver, far less than their normal price. In Philobiblon

"Richard de Bury gives an account of the wearied efforts made by himself and his agents to collect books. He records his intention of founding a hall at Oxford, and in connection with it a library in which his books were to form the nucleus. He even details the dates to be observed for the lending and care of the books, and had already taken the preliminary steps for the foundation. The bishop died, however, in great poverty on 14 April 1345 at Bishop Auckland, and it seems likely that his collection was dispersed immediately after his death. Of it, the traditional account is that the books were sent to the Durham Benedictines Durham College, Oxford which was shortly thereafter founded by Bishop Hatfield, and that on the dissolution of the foundation by Henry VIII they were divided between Duke Humphrey of Gloucester's library, Balliol College, Oxford, and George Owen. Only two of the volumes are known to be in existence; one is a copy of John of Salisbury's works in the British Museum, and the other some theological treatises by Anselm and others in the Bodleian.

"The chief authority for the bishop's life is William de Chambre, printed in Wharton's Anglia Sacra, 1691, and in Historiae conelmensis scriptores tres, Surtees Soc., 1839, who describes him as an amiable and excellent man, charitable in his diocese, and the liberal patron of many learned men, among these being Thomas Bradwardine, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury, Richard Fitzralph, afterwards Archbishop of Armagh, the enemy of the mendicant orders, Walter Burley, who translated Aristotle, John Mauduit the astronomer, Robert Holkot and Richard de Kilvington. John Bale and Pits I mention other works of his, Epistolae Familiares and Orationes ad Principes. The opening words of the Philobiblon and the Epistolaeas given by Bale represent those of the Philobiblon and its prologue, of that he apparently made two books out of one treatise. It is possible that the Orationes may represent a letter book of Richard de Bury's, entitled Liber Epistolaris quondam dominiis cardi de Bury, Episcopi Dunelmensis, now in the possession of Lord Harlech.

"This manuscript, the contents of which are fully catalogued in the Fourth Report (1874) of the Historical Manuscripts Commission (Appendix, pp. 379–397), contains numerous letters from various popes, from the king, a correspondence dealing with the affairs of the university of Oxford, another with the province of Gascony, beside some harangues and letters evidently meant as models to be used on various occasions. It has often been asserted that the Philobiblon itself was not written by Richard de Bury at all, but by Robert Holkot. This assertion is supported by the fact that in seven of the extant manuscripts of Philobiblon it is ascribed to Holkote in an introductory page, in these or slightly varying terms: Incipit prologus in re philobiblon ricardi dunelmensis episcopi que libri composuit ag. The Paris manuscript has simply Philobiblon olchoti anglici, and does not contain the usual concluding note of the date when the book was completed by Richard. As a great part of the charm of book lies in the unconscious record of the collector's own character, the establishment of Holkot's authorship would materially alter its value. A notice of Richard de Bury by his contemporary Adam Murimuth (Continuatio Chronicarum, Rolls series, 1889, p. 171) gives a less favourable account of him than does William de Chambre, asserting that he was only moderately learned, but desired to be regarded as a great scholar (Wikipedia article on Richard de Bury, accessed 02-04-2014).

Philobiblon was published in print for the first time in Cologne, 1473.