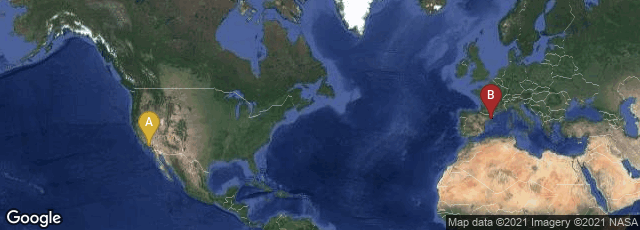

A: Los Angeles, California, United States, B: Barcelona, Catalunya, Spain

On February 10, 2011 social scientist Martin Hilbert of the University of Southern California (USC) and information scientist Priscilla López of the Open University of Catalonia published "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information." The report appeared first in Science Express; on April 1, 2011 it was published in Science, 332, 60-64. This was "the first time-series study to quantify humankind's ability to handle information." Notably, the authors did not attempt to address the information processing done by human brains—possibly impossible to quantify at the present time, if ever.

"We estimated the world’s technological capacity to store, communicate, and compute information, tracking 60 analog and digital technologies during the period from 1986 to 2007. In 2007, humankind was able to store 2.9 × 10 20 optimally compressed bytes, communicate almost 2 × 10 21 bytes, and carry out 6.4 × 10 18 instructions per second on general-purpose computers. General-purpose computing capacity grew at an annual rate of 58%. The world’s capacity for bidirectional telecommunication grew at 28% per year, closely followed by the increase in globally stored information (23%). Humankind’s capacity for unidirectional information diffusion through broadcasting channels has experienced comparatively modest annual growth (6%). Telecommunication has been dominated by digital technologies since 1990 (99.9% in digital format in 2007), and the majority of our technological memory has been in digital format since the early 2000s (94% digital in 2007)" (The authors' summary).

"To put our findings in perspective, the 6.4 × 10 18 instructions per second that humankind can carry out on its general-purpose computers in 2007 are in the same ballpark area as the maximum number of nerve impulses executed by one human brain per second (10 17 ). The 2.4 × 10 21 bits stored by humanity in all of its technological devices in 2007 is approaching an order of magnitude of the roughly 10 23 bits stored in the DNA of a human adult, but it is still minuscule as compared with the 10 90 bits stored in the observable universe. However, in contrast to natural information processing, the world’s technological information processing capacities are quickly growing at clearly exponential rates" (Conclusion of the paper).

"Looking at both digital memory and analog devices, the researchers calculate that humankind is able to store at least 295 exabytes of information. (Yes, that's a number with 20 zeroes in it.)

"Put another way, if a single star is a bit of information, that's a galaxy of information for every person in the world. That's 315 times the number of grains of sand in the world. But it's still less than one percent of the information that is stored in all the DNA molecules of a human being. 2002 could be considered the beginning of the digital age, the first year worldwide digital storage capacity overtook total analog capacity. As of 2007, almost 94 percent of our memory is in digital form.

"In 2007, humankind successfully sent 1.9 zettabytes of information through broadcast technology such as televisions and GPS. That's equivalent to every person in the world reading 174 newspapers every day. On two-way communications technology, such as cell phones, humankind shared 65 exabytes of information through telecommunications in 2007, the equivalent of every person in the world communicating the contents of six newspapers every day.

"In 2007, all the general-purpose computers in the world computed 6.4 x 10^18 instructions per second, in the same general order of magnitude as the number of nerve impulses executed by a single human brain. Doing these instructions by hand would take 2,200 times the period since the Big Bang.

"From 1986 to 2007, the period of time examined in the study, worldwide computing capacity grew 58 percent a year, ten times faster than the United States' GDP. Telecommunications grew 28 percent annually, and storage capacity grew 23 percent a year" (http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/02/110210141219.htm)