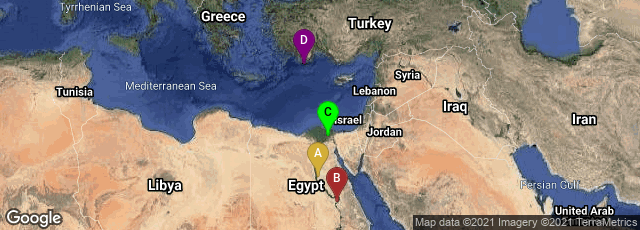

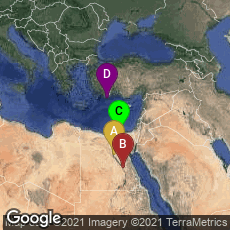

A: Menia Governorate, Egypt, B: Luxor Governorate, Egypt, C: Ash Sharqia Governorate, Egypt, D: Turkey

Archaeological evidence and the analysis of ancient sources point to a Mesopotamian origin for glassmaking around 2500 BCE. This craft and its makers migrated to Egypt around 1400 BCE where glassmaking soon developed as an independent technology.

"Glass beads are known from the 3rd millennium BC but it is only in the late 2nd millennium that glass finds start occurring more frequently, primarily in Egypt and Mesopotamia. This is not to say that it was a widespread commodity, quite the contrary. It was a material for high-status objects with archaeological evidence for the Late Bronze Age (LBA) also showing an almost exclusive distribution of glass finds at palace complexes such as that found in the city of Amarna - Egypt. Texts listing offerings to Egyptian temples would start with gold and silver, followed by precious stones (lapis lazuli) and then bronze, copper and other not so precious stones with glass mentioned together with the lapis lazuli. In this period it was rare and precious and its use largely restricted to the elite.

"Production of raw glass occurred at primary workshops of which only 3 are known, all in Egypt: Amarna, Ramesside [place?] and Malkata. At the first two sites cylindrical ceramic vessels with vitrified remains have been identified as glass crucibles where the raw materials (quartz pebbles and plant ash) would be melted together with a colourant. Interestingly the two sites seem to show a specialisation in colour, with blue glass, via the addition of cobalt, being produced at Amarna and red, through copper, at Piramesse. The resulting coloured glass would then be fashioned into actual objects at secondary workshops - far more common in the archaeological record. It seems certain that glass making was not exclusive to Egypt (in fact current scholarly opinion resides with the industry having originally been imported into the country) as there are Mesopotamian cuneiform texts which detail the recipes for the making of glass. Further supporting this hypothesis are the Amarna Letters, a contemporaneous diplomatic correspondence detailing the demand and gift giving from vassal princes in Syro-Palestine to the Egyptian King, in these the most asked for item is glass.

The evidence then points to two regions that were making and exchanging glass. It seems logical to believe that at an initial stage it was glass objects, as opposed to raw glass, that were exchanged. The major element composition of glass finds from Mesopotamia and Egypt is indistinguishable with as much variation found within a specific assemblage than between different sites. This is indicative of the same recipe being used in both regions. As analytical techniques develop the presence of trace elements can be more accurately determined and it has been found that glass is compositional identical within each region, but it is possible to discriminate between them. This could be a huge step in uncovering trade patterns, however at present no Egyptian glass has been found in Mesopotamia, nor have any Mesopotamian glasses been found in Egypt.

"Across the sea, Mycenaean glass beads were found to have been made with glass from both regions. The fact that the beads are stylistically Mycenaean would imply an import of raw glass. Archaeological evidence for this trade comes from the Uluburun shipwreck, dated to the 14th century BC. As part of its cargo it carried 175 raw glass ingots of cylindrical shape. These ingots match the glass melting crucibles found at Amarna and Piramesse [Pi-Rammesse] " (Wikipedia article on Ancient Glass Trade, accessed 01-12-2012).