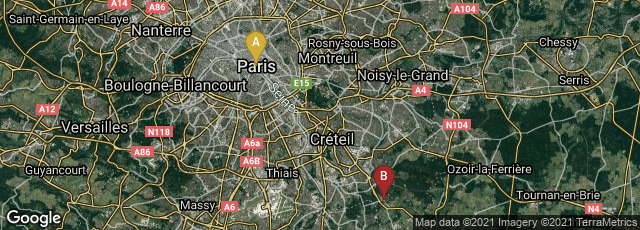

A: Paris, Île-de-France, France, B: Boissy-Saint-Léger, Île-de-France, France

La chymie charitable et facile, en faveur des dames, a book on practical chemistry, pharmacology and medicine written for the common reader, written by French autodidact Marie Meurdrac (?1610-1680) and first published in Paris in 1666, was the first treatise on chemistry written by a woman. Clearly a work that found a wide market, it underwent five editions in French, the last of which was published in 1711, six editions in German, and one in Italian.

Little is known about Meurdrac except that she was born into an aristocratic French family in north-central France, and that in 1625 she married Henri de Vibrac, commander of the guard unit of Charles de Valois, Duke of Angoulême. Valois was the illegitimate son of Charles IX of France and Marie Touchet. As part of the Duke's retinue, Meurdrac lived in the château de Grosbois in Boissy-Saint-Léger, Val-de-Marne.

"In the lengthy foreword, Meurdrac candidly reveals her hesitation about publishing the treatise that had been intended solely as a permanent record of her research. Further, she questions the larger issue of a woman's right to publish and its ensuing consequences. 'I remained irresolute in this inner struggle fro two years,' she writes. 'I objected to myself that it was not the profession of a lady to teach, that she should remain silent, listen and learn, without displaying her own knowledge. . . that a reputation gained thereby is not ordinarily to her advantage since mean always scorn and blame the products of a woman's mind.' Meurdrac ultimately decided to go public as Damoiselle [sic] M. M., declaring that 'minds have no sex and that if the minds of women were cultivated like those of men and if enough time and expense were spent to instruct them, they would be equal to those of men.

"Her decision to publish was rooted in her unwavering belief that her practical book was useful remedying women's illnesses as well as a guide to the presevation of their health. Unquestionably an early feminist who broke ground in an area where few women dared to tread, Meurdract felt that not sharing knowledge that should ameliorate the lives of others would be a betrayal of the Catholic principle of charity as well as incompatible with her inquistive temperament. A true seventeenth-century femme savante, Meurdrac, along with other learned women, who were later ridculed in Molière's comedy Les Femmes Savantes (1672), would not be deterred in the quest to investigate, comprehend, and contribute to the advancement of scholarship" (Smeltzer, Ruben & Rose, Extraordinary Women in Science & Medicine, New York: The Grolier Club, 2013, No. 85, p. 94).

A few copies of this work bear the date of 1656 on their title pages, leading to the impression that the first edition was published in 1656. However, those copies bear the imprimatur dated 1666 like the rest of the edition, showing that the 1655 date was a typographical error, corrected in most copies.

(This entry was last revised on 06-15-2014.)