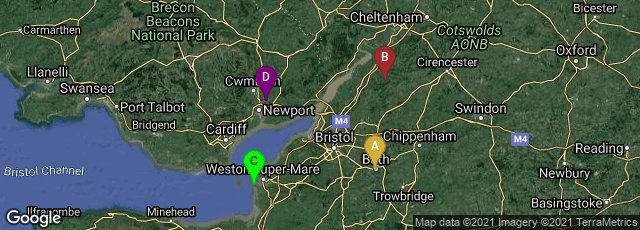

A: Bath, England, United Kingdom, B: Uley, Dursley, England, United Kingdom, C: Burnham-on-Sea, England, United Kingdom, D: Caerleon, Newport, Wales, United Kingdom

In 1979 and 1980, the Bath curse tablets (tabella defixionis, defixio) were excavated from the sacred hot spring at the Aquae Sulis in the Roman province of Britannia (now Bath, England). The 130 tablets or defixiones, inscribed on thin sheets of pewter, primarily invoked the intercession of the goddess Sulis Minerva for the return of belongings or money stolen while the victim was bathing. Their language is of special value as examples of the everyday spoken vernacular of the Romano-British population during the second to fourth centuries CE. Since the language on these tablets came to light this language became known as "British Latin."

While most texts from Roman Britain are in Latin, two scripts found at Aquae Sulis, written in Roman lettering on pewter sheets, are in an unknown Celtic language, which may be Brythonic— the only examples of writing in what is thought to be the unwritten language of the Celtic people known as the Britons.

"All but one of the 130 Bath curse tablets concern the restitution of stolen goods and are a type of curse tablet known as 'prayers for justice.' The complaints of thefts are generally of personal possessions from the baths such as jewelry, gemstones, money, household goods and especially clothing. Theft from public baths appears to have been a common problem as it was a well-known Roman literary stereotype and severe laws existed to punish the perpetrators. Most of the depositors of the tablets (the victims of the thefts) appear to have been from the lower social classes.

"The inscriptions generally follow the same formula, suggesting they were taken from a handbook: the stolen property is declared as having been transferred to a deity so that the loss becomes the deity’s loss; the suspect is named and, in 21 cases, so is the victim; the victim then asks the deity to visit afflictions on the thief (including death) not as a punishment but to induce the thief to hand the stolen items back. The deity whose help was invoked is Sulis, and the tablets were deposited by the victims in the spring that was sacred to her" (Wikipedia article on Bath Curse Tablets, accessed 07-13-2014).

Over eighty other Roman curse tablets were discovered in and about the remains of a temple to Mercury at West Hill, Uley, making south-western Britain one of the major centers for finds of Latin defixiones. Smaller numbers of tablets were also found at the the sites of Roman temples at Lydney (Gloucestershire), Brean Down (Somerset), the Pagans Hill Roman Temple (Somerset), the amphitheatre of the legionary fortress of Isca Augusta at Caerleon, South Wales, and the small towns at Chesterton-on-Fosse (Warwickshire) and Leintwardine (Herefordshire).

In July 2014 images, transcriptions, and English translations of many of the tablets were available from the Curse Tablets from Roman Britain website operated by the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents at Oxford.