William Morris' s Hopkinson & Cope Albion iron hand press manufactured in London in 1891 that was used to print the books issued by Morris's Kelmscott Press. The press later belonged to Frederick Goudy. It is preserved at the Cary Graphic Arts Collection at Rochester Institute of Technology.

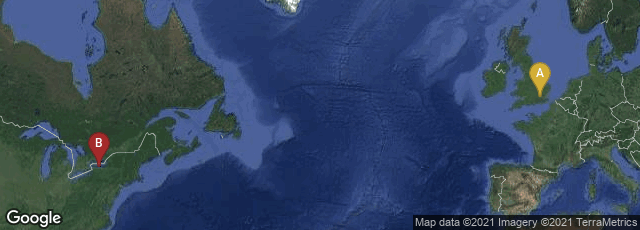

A: London, England, United Kingdom, B: Rochester, New York, United States

In 1892 William Morris issued an edition of John Ruskin's The Nature of Gothic from his Kelmscott Press in Hammersmith, with an introduction written by Morris. Printed by hand-press on handmade paper in Morris's Golden Type inspired by the 15th century printer Nicolas Jenson, Morris's edition was the most notable fine press edition of a work that became a kind of manifesto for the Arts and Crafts movement. Morris used a London-built Hopkinson & Cope Improved Albion Press (No. 6551) built in 1891. That Hopkinson & Cope were still manufacturing Albion presses in 1891 exemplifies the persistence of hand press printing throughout the 19th century and its continuation for short run purposes into the 20th, and even into the 21st.

The Arts and Crafts movement, which flourished in Europe and North America between 1880 and 1920, was an international movement in decorative and fine arts that promoted traditional craftsmanship in opposition to factory production and its social and economic impacts that resulted from the Industrial Revolution. The contrast in physical characteristics and quality between Morris's superbly hand-produced limited editions issued in opposition to mass production, and mass-produced publications issued as a result of the Industrial Revolution, was more than obvious.

In this chapter from the second volume of Ruskin's The Stones of Venice (1851-53), Ruskin argued that Gothic ornament "was an expression of the artisan's joy in free, creative work. The worker must be allowed to think and to express his own personality and ideas, ideally using his own hands, not machinery.

We want one man to be always thinking, and another to be always working, and we call one a gentleman, and the other an operative; whereas the workman ought often to be thinking, and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen, in the best sense. As it is, we make both ungentle, the one envying, the other despising, his brother; and the mass of society is made up of morbid thinkers and miserable workers. Now it is only by labour that thought can be made healthy, and only by thought that labour can be made happy, and the two cannot be separated with impunity.

"This was both an aesthetic attack on, and a social critique of the division of labour in particular, and industrial capitalism in general. This chapter had a profound impact, and was reprinted both by the Christian socialist founders of the Working Men's College and later by the Arts and Crafts pioneer and socialist, William Morris.[41]"(Wikipedia article on Arts and Crafts movement, accessed 11-2-2018).