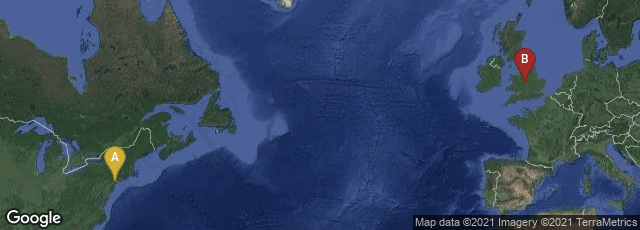

A: Brooklyn, New York, United States, B: Birmingham, England, United Kingdom

In 1863 inventor William H. Mitchel of Brooklyn, NY published an extended paper in pp. 34-53 of the Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers entitled on a "Type Composing and Distributing Machine". Mitchel's paper, describing his machine and the advantages it offered in the context of the manual typesetting challenges of the time, was illustrated with 7 schematic engravings.

As far as I have been able to determine, Mitchel's was the first paper on the problems of mechanizing and distributing metal types published by one of the inventors of this equipment. Mitchel, who had patented his machines in 1853, and had overseen their application in various printing establishments, as reported by William Winter (1864), had travelled across the Atlantic to promote his machines. Mitchel's machines were the first to be extensively used in America, chiefly on repetitive style of work. By 1863 it is possible that Mitchel's machines had done more actual typesetting than any typesetting machine invented in Europe.

Mitchel began his paper, presented and published in England, by estimating that 50 million pieces of type were handset in England daily--an enormous amount of hand typesetting that employed many thousands of people. He also estimated that since the development of printing machines the amount of printing done had increased by one hundred fold over printing by the hand-press.

"Athough the process of printing from moveable types has by the power press been accelerated a hundred fold, the art of composing the types in order to be printed from has not advanced a step since Gutenberg's time. About fifty millions of letters daily are composed and distributed in the United Kingdom; and every one of these is picked from a box by the fingers, and afterwards returned to it in the same manner, without any sort of mechanical aid. Nevertheless during the last twenty years fully twenty attempts have been made by English, French, German Danish, Italian, and American inventors to effect an economy in this direction. Three inventors have died recently, after devoting seventeen and eighteen years respectively to this subject, and have left the eventual introduction ofmachinery for composition still a question, and one which printers in general yet decide in the negative. In order to appreciate the efforts of these numerous inventors it is necessary to have a clear idea of the nature of the work to be performed.

"The work of the compositor may be divided into five operations:— Composition, Justification, Making up. Correction, and Distribution....

"These five operations represent the work of the compositor in about the following proportions:—

Composition . . . 55 per cent

Justification . . . 17 "

Making up . . . 7 "

Correction . . . 7 "

Distribution . . . 14 "

"Of these processes, justification, making up, and correction have never been attemped by machinery. The fifth, distribution, is already very rapidly effected by hand, so that no much scope is left for saving of labour; but inasmuch as all composing machines require the letters to be primarily dispoed in lines ready for setting up, it has been found necessary to use machinery to distribute them in that manner.

After a very long explanation of the process of typesetting by his machines, Mitchel explained that the use of typesetting machinery could result in a 43% cost saving over manual typesetting, but only if the machines available at this time were used for basic, repetitive style of typesetting without changes of type size or type style.

"The economic bearing of these composing and distributing machines, and the results actualy obtained in work done where they have already come into use, remain now to be considered. Of the numerous inventions for the same purpose that have been brought forwards at intervals within the last twenty years, some were the subject of much attention; and several were for a time at work, more or less experimentally, but afterwards fell into disuse. And in the case of the machines now exhibited [Mitchel's machines], their progress during the nine years they have been in existence must be regarded as extremely slow. It might have been expected, from the undoubted advantage possessed by finger keys over the hand picking-up process, that a saving would be effected large enough at once to overbear all objection, and lead to the speedy and general introduction of the machines. But this is not the case. The savings has never exceeded 50 per cent., diminishing under less favourable circumstances to little or nothing; while the difficulty of adapting the new method of composition to the present conditions of printing has been very great. That the saving falls short of what might be anticipated is owing to the circumstance that the work of the compositor consists as already stated of several distinct operations, some of them susceptible of mechanical aid, but others either not suceptible or hitherto unattempted. What makes the difficulty great is that it is not easy to separate one operation from another. For instance it is inconvenient to charge one compositor with the justification or correction of work composed by another; consequently it is impossible to introduce that division of labour indispensable for obtaining the full benefit of machinery. The compositor has thus to pass from an operation in which he is assisted by mechanism to others which are purely manual; and one result of this shifting about is that the machine stands idle about one fourth of each day. A still more serious result is the waste of time inevitable wherever there is frequent changing from one process to another. The mere setting of the types in line, in which alone a savings is effected, amounts as been stated to about 55 per cent, of the whole work; but even this includes the operation of reading the copy, which cannot be accelerated by machinery; so that the actual fingering of the keys is reduced to about 50 per cent of the gross work. Supposing therefore that the compositor is enabled by the keys to set up seven letters for one that he could set up by hand, there results only a saving of about 43 per cent. on the whole process.

"Another difficulty arises from the extremely irregular and fluctuating supply of work of any given character in printing establishments. Unlike other extensive trades there is in this but little classification. Every printing office undertakes every description of work, from a card to a book. But composing machines are not suited for doing cards, nor for what is called 'displayed work' nor in fact for anything but tolerably plain straightforward work; so that frequent variations in the characer of the supply are for machines very inconvenient. If these machines could, like the power loom, be kept regularly supplied with suitable work, their success would be assured notwithstanding all drawbacks...."