A: Città del Vaticano, Vatican City

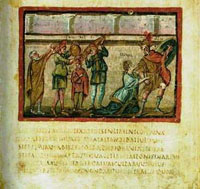

The Vergilius Vaticanus (Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica, Cod. Vat. lat. 3225; also known as the Vatican Virgil or Vatican Vergil)t written in Rome in rustic capitals toward the end of the fourth century, containing fragments of Vergil's (Virgil's) Aeneid and Georgics. It is one of the oldest sources for the text of the Aeneid, and one of the oldest surviving illustrated codices on any subject. Therefore some of its images represent firsts in book illustration. For example, the image of the seige of Troy on leaf 19 recto is probably the oldest image of warfare in a codex. The codex has been called "the most important surviving ancient example of an illustrated book of classical literature" (D.H. Wright).

The Vatican Virgil is also the oldest of three surviving lllustrated manuscripts of classical literature. The two others are the Vergilius Romanus (circa 450) and the Ambrosian Iliad (Ilias Ambrosiana) (493-508). Before passing into the Vatican Library, the Vergilius Vaticanus, of which seventy-five leaves survive, belonged to the humanist and poet, Giovanni Giovano Pontano, to the poet, literary theorist and cardinal Pietro Bembo, and to the humanist, historian and archaeologist, Fulvio Orsini.

"It is Italy that has left us the greatest legacy of books and literature from the late Roman world. In the Italy of the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries there were probably still stationers who employed scribes to produce books and well as scribes and artists who worked independently. The Codex Vaticanus [same as Vergilius Vaticanus] of Virgil and the Quedlinburg fragment of the Book of Kings in the Vetus Latin version are two products of this professional scribal activity from the end of the fourth century. Both manuscripts might have originated in the same scriptorium" (Bernhard Bischoff, Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne [2007] 3-4).

Note: In his dating of the Quedlinburg fragment, and his consideration that both might have been produced by the same shop, Bischoff, who originally wrote his essays in German between 1966 and 1981, differs from later scholarship.

"Even as the Roman empire collapsed, literate men acknowledged that the Christianized Virgil was a master poet.. . . . The Aeneid remained the central Latin literary text of the Middle Ages and retained its status as the grand epic of the Latin peoples, and of those who considered themselves to be of Roman provenance, such as the English. It also held religious importance as it describes the founding of the Holy City. Virgil was made palatable for his Christian audience also through a belief in his prophecy of Christ in his Fourth Ecologue. Cicero and other classical writers too were declared Christian due to similarities in moral thinking to Christianity.

•"In the Middle Ages, Virgil was considered a herald of Christianity for his Ecologue 4 verses (Perseus Project Ecl.4) concerning the birth of a boy, which were read as a prophecy of Jesus' nativity.

•"Also during the Middle Ages, as Virgil was developed into a kind of magus, manuscripts of the Aeneid were used for divinatory bibliomancy, the Sortes Virgilianae, in which a line would be selected at random and interpreted in the context of a current situation" (Wikipedia article on Virgil, accessed 12-03-08).

Possibly coincident with the type facsimile publication in 1741 of the text of the fifth century Codex Mediceus of Virgil, an edition of the illustrations of the Vergilius Vaticanus and the Codex Romanus engraved by Pietro Santi Bartoli was published in Rome: Antiqvissimi Virgiliani codicis fragmenta et picturae ex Bibliotheca Vaticana : ad priscas imaginum formas a Petro Sancte Bartholi incisae. Romae : ex Chalcographia R.C.A., apud Pedem Marmoreum, 1741. This contained 58 engraved plates reproducing images from the Vergilius Vaticanus plus 6 additional illustrations from the Codex Romanus. Catalogue records indicate that Bartoli's images may have been first published separately in 1677.

In 1782 Bartoli's engravings were reissued in an excellent edition combining images from both Virgil manuscripts together with related images from ancient engraved gems depicting events in Virgil. The new edition was entitled Picturae antiquissimi Virgiliani codicis Bibliothecae Vaticanae a Petro Sancte Bartoli aere incisae accedunt ex insignioribus pinacothecia picturis aliae veteres gemmae et anaglypha, and published in Rome by Venantius Menaldini. The frontispiece, engraved title and dedication of this edition are spectacular. The 1782 edition contains 124 images plus the engraved frontispiece, title, and dedication.

In 1899 the Vatican Library issued a black and white facsimile of the Vatican Vergil as the first of its facsimile series, Codices e vaticanis selecti phototypice expressi, vol. 1. In 1980 they followed this with a facsimile in color as Codices e vaticanis selecti phototypice expressi, vol. 40. The best and most exact facsimile was issued by Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria in 1984. That edition reproduced the manuscript and its 19th century red morocco binding precisely, and included a commentary volume in English by David H. Wright. The definitive study of the manuscript, which places it within the artistic and cultural context of its time, is Wright's The Vatican Vergil. A Masterpiece of Late Antique Art (1993).

Reynolds, Texts and Transmission. A Survey of the Latin Classics (1983) 434.