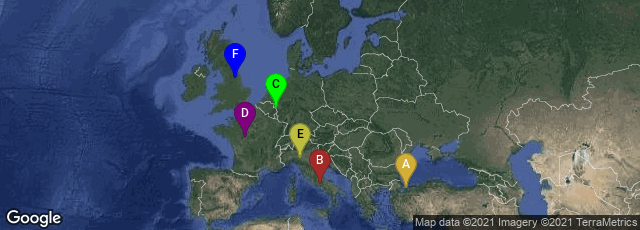

A: İstanbul, Turkey, B: Lazio, Italy, C: Mitte, Aachen, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, D: Tours, Centre-Val de Loire, France, E: Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, F: York, England, United Kingdom

"Charlemagne and the Monastic Scribes." Painting by Robert Thom from the series Graphic Communications Throughout the Ages preserved in the Cary Graphic Arts Collection at Rochester Institute of Technology.

"The classical revival of the late eighth and early ninth centuries, without doubt the most momentous and critical stage in the transmission of the legacy of Rome, was played out against the background of a reconstituted empire which stretched from the Elbe to the Ebro, Calais to Rome, welded together for a time into a political and spiritual whole by the commanding personality of an emperior who added to his military and material resources the blessing of Rome. Although the political achievement of Charlemagne (768-814) crumbled in the hands of his successors, the cultural movement which it fostered retained its impetus in the ninth century and survived into the tenth.

"The secular and ecclesiastical administration of a vast empire called for a large number of trained priests and functionaries. As the only common denominator in a heterogeneous realm and as the repository of both the classical and the Christian heritage of an earlier age, the Church was the obvious means of implementing the educational program necessary to produce a trained executive. But under the Merovingians the Church had fallen on evil days; some of the priests were so ignorant of Latin that Boniface heard one carrying out a baptism of dubious efficacy in nomine patria et filia et spiritus sancti (Epist. 68), and knowledge of antiquity had worn so thin that the author of one sermon was under the unfortunate impression that Venus was a man. Reform had begun under [Charlemagne's father] Pippin the Short; but now the need was greater, and Charlemagne felt a strong personal responsibility to raise the intellectual level of the clergy, and through them of his subjects. . . ." (Reynolds & Wilson, Scribes and Scholars 3rd ed [1991] 92-93).

In 780, at Parma Charlemagne, King of the Franks, met the Anglo-Saxon monk Alcuin, who was head of the episcopal school at the Cathedral of York. Charlemagne took scholarship seriously. He had learned to read as an adult, although he never quite learned how to write. At this time of reduced literacy outside of the clergy, writing of any kind was an achievement for kings, many of whom were illiterate.

Recognizing that Alcuin was a scholar who could help him achieve a renaissance of learning and reform of the Church, in 782 Charlemagne induced Alcuin to move to the royal court as Master of the Palace School at Aachen, where Alcuin remained until 796. This school was attended by members of the royal court and the sons of noble families. At Aachen Alcuin established a great library, for which Charlemagne obtained manuscripts from Monte Cassino, Rome, Ravenna and other sources.

"Books are naturally attracted to centres of power and influence, like wealth and works of art and all that goes with a prosperous cultural life. Some arrive as the prerequisites of conquest, or as the gifts that pour in unasked when the powerful have made thier wishes plain, some in response to the magnetic pull of an active and dynamic cultural movement. Others were actively sought out by those promoting the educational and cultural aims of the revival. There was such a break in the copying of the classics in the Dark Ages that many of the books that provided the exemplars from which the Carolingian copies were made must have been ancient codices, and this immediately raises a fundamental question; where did all the books that have salvaged so much of what we have of Latin literature come from? As far as we can tell from the evidence available, the total contribution of Ireland and England, Spain and Gaul, was small in comparison with what came from Italy itself, from Rome and Campania and particularly, it would seem, from Ravenna after its capture by the forces of Charlemagne. Nor did the wholesale transference of classical texts to northern Europe exhaust the deposits in Italy, for Italy continued, down to the end of the Renaissance and beyond, to produce from time to time texts which, as far as we can tell, had been unknown north of the Alps.

"Gathering impetus with each decade, the copying of books went on apace through the length and breadth of Charlemagne's empire. Such ancient classical manuscripts as could be found, with their imposing majuscule scripts, were transformed, often at speed, into minuscule copies, and these in time begot further copies, branching out into these complex patterns to which the theory of stemmatics has reduced this fascinating process. The routes by which texts travelled as they progressed from place to place were naturallty governed in part by geographical factors, as they moved along the valleys of the Loire or Rhine, but even more by the complex relationships that existed between institutions and the men who moved between them. There are so many gaps in our knowedge, and so many of pieces in this puzzle have been irrevocably lost, that we can never hope to build up a convincing distribution map for the movements of texts in this period. But certain patterns are discernible, and the drift of texts south and west through the Low Countries and northern France, and down the Rhine to the shores of Lake Constance, appears to point to a fertile core in the area of Aachen, and this would confirm the crucial importance of the palace as a centre and a catalyst for the dissemination of classical texts" (Reynolds & Wilson, op. cit. 97-98).

Also at Aachen, and later at Tours to which he retired in 796, Alcuin promoted the development of the Carolingian minuscule, which became the writing standard for the eighth and ninth centuries.

"The use. . . of a script more compact in the body and needing less time to write, may have been decided upon in view of the plans to proceed with a State educational project, the greatest ever undertaken in the West, or perhaps anywhere at any time in the Roman Empire. For such an enterprise the employment of an accelerated script would become an interest of State, or, to be accurate, of State and Church" (Morison, Politics and Script. . . . Barker ed. [1972] 143).

Regarding the origin of Carolingian minuscule there is little consensus. In the words of palaeographer Stan Knight:

"Some authorities detect Roman (ie.half-uncial) roots, others French pre-Carolingian, some even see Insular influence (perhaps seeking a link with Alcuin), others cursive or semi-cursive scripts. Various combinations of these influences are also suggested. The opinions are many and bewildering.

"The problem is made more complicated because the actual emergence of Carolingian minuscule appears to have been rather haphazard. There is no solid evidence to suggest that it emanated from just one center, nor can any systematic development of the script be discerned (apart from the natural maturing observable in the work of energetic scriptoria like that at Tours). . . . My considered opinion is that Carolingian minuscule was a modification of the ancient and serviceable half-uncial script, incorporating certain features gathered from other current scripts, and that the Abbey of Corbie led the field in this vitally important calligraphic development" http://dh101.humanities.ucla.edu/DH101Fall12Lab1/items/show/8, accessed 08-07-2014).

Alcuin revised the church liturgy, and also revised Jerome's translation of the Bible. Alcuin and his associates— particularly the Visigothic writer, poet and bishop Theodulf of Orleans, who produced his own, competing, edition of the Bible — were responsible for an intellectual movement within the Carolingian Empire in which many schools were attached to monasteries and cathedrals, and Latin was restored as a literary language. Along with these schools there was a flowering of libraries and manuscript book production.

Charlemagne's Admonitio generalis, a collection of legislation known as a capitulary issued in 789, covered educational and ecclesiastical reform within the Frankish kingdom, established his religious and educational aspirations for the kingdom, and became a foundation for the Carolingian Renaissance.

"Before the surge of education following the Admonitio Generalis and subsequent Carolingian Renaissance, it was difficult for the Frankish people to connect with Christianity and the church. Peasant life was very hard; the people were illiterate and Latin, the language of the church, was not their native language, making Christianity and the Bible difficult to access. Nobles also were largely uneducated and uncultured, with few devoted Christians among them. Only the clergy were consistent in having some level of education, and thus they had the best understanding and exposure to the Bible and the full extent of Christianity. The schools, which the Admonitio ordered established by the monasteries and cathedrals, began a tradition of higher learning in Carolingian Europe, leading the revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The fulfillment of Admonitio Generalis meant that the study of language, rhetoric and grammar in these institutions, as well as the standardizing of writing scripture and Latin, was undertaken in order to make religious texts and books accessible to the clergy, as well as their correction and standardization. However this strengthened all forms of Carolingian literature, and book production, as well as developments in law, historical writing, and uses of poetry all flourished in these schools. In fact, the capitularies themselves, and the level of language they use, are examples of the increasing importance of writing within the Frankish kingdom. As well as language, the Admonitio Generalis ordered other arts such as numbers and arithmetic, ratios, taxes, measure, architecture, geometry, and astrology to be taught, leading to developments in each field and their application within society. Charlemagne pushed for an educated clergy who could help lead reform, because it was his belief that the study of arts would aid them in understanding sacred texts, which they could then pass on to their followers. During the Carolingian Renaissance, Charlemagne unified religious practices and culture within his realm, creating a Christian kingdom, and ultimately unifying his empire" (Wikipedia article on Admonitio Generalis, accessed 08-06-2014).

"The Carolingian programme of renewal was consciously based on Antiquity. Order and stability lay in a vigorous revival of that which was useful and applicable from the Roman past: e.g. its imagery and art forms, such as the human figure as the central theme of art, or its reliance on the written word. Although, culturally, its upward trajectory had peaked by AD 877, this Carolingian renewal had by then insured the survival of ancient art and literature. The text of virutally every ancient Latin author is today edited largely from Carolingian manuscripts. Texts of only a handful of ancient authors—Tibullus, Propertius, Catullus among them—are not reconstructed from manuscripts of the Carolingian renaissance" (Rouse, "The Transmission of the Texts," Jenkyns ed. The Legacy of Rome: A New Appraisal [1992] 46-47).

(This entry was last revised on 08-19-2014).