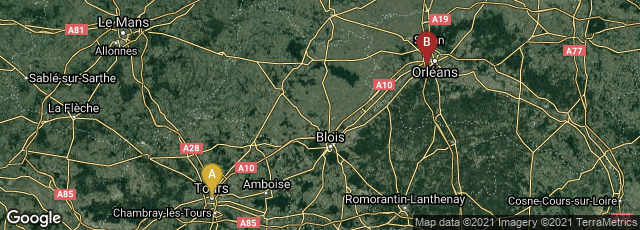

A: Tours, Centre-Val de Loire, France, B: Saint-Pryvé-Saint-Mesmin, Centre-Val de Loire, France

Frontispiece to Genesis, depicting the Creation of Adam and Eve, their Temptation and Expulsion from the idealised landscape of Eden to labour on thorny soil, from the Moutier-Grandval Bible, France (Tours), c. 830 – c. 840, British Library Add MS 10546, f. 5v

Bibles were the longest text widely copied during the Middle Ages, and by medieval standards the production of two whole manuscript Bibles per year by one scriptorium— specifically that at Tours— may be considered "mass production." In addition to Bibles the Tours scriptorium also produced copies of many of liturgical and classical texts. Tours Bible production levels were particularly remarkable in view of the quality of the calligraphy, and richness of decoration and illumination characteristic of some of these Bibles. Of the nearly 100 Bibles produced at Tours during the first 60 years of the ninth century three illuminated Bibles survived, among which perhaps the most outstanding is the Moutier-Grandval Bible.

From David Ganz's chapter 3, "Mass production of early medieval manuscripts: the Carolingian Bibles from Tours" in Gameson, ed., The Early Medieval Bible (1994) 53-55 I quote selections, with my habitual addition of links. The footnotes are, as usual, excluded:

"The copying of complete texts of the Bible, contained in only one or two volumes, which characterised the scriptoria of St. Martin's and Marmoutiers at Tours during the course of the ninth century, constituted a new development in medieval book production. While multi-volume and single-volume Bibles had been copied before, and the scriptorium at Wearmouth-Jarrow had made three copies of the Bible, whose layouts and similarities await study, the multiple reproduction of the biblical text during a sixty year period cannot be paralleled. Only the attempt by the abbey of Micy to provide several copies of the Bible recension prepared by Theodulf of Orléans deserves mention here. Theodulf's text was continuously revised during his lifetime, and was conceived as an accessible reference work, and so he chose a very small, three column 61-line format, with quires of five leaves. The copying involved elaborate scribal preparation, and the Bibles were produced within a short space of time. Six copies survive and two others have left traces, and there is clear evidence that Theodulf's text was used to improve biblical texts throughout the Carolingian empire.

"Carolingian book production was decisively affected by the steady supply of Bibles and gospel books which were copied at Tours. Forty-six Bibles and eighteen gospel books have survived from the period before 853; only three Bibles and seven gospel books may be dated later in the ninth century, an indication of the severe effects of Viking attacks on Tours in the reign of Charles the Bald, notably the burning of St. Martin's Abbey in 853, 872, and again in 903. So the Tours scriptoria were perhaps copying two full Bibles per year, for more than half a century. Nor was book production at Tours restricted to these Bibles: the abbey of St. Martin was also copying the works of classical, patristic and Carolingian authors. Works of Cicero, Servius, Hegesippus, Augustine, Orosius, Priscian, Isidore, the Paris Council of 829, Amalarius, Paul the Deacon, were all copied between 820 and 860. What has not been sufficiently acknowledged is that many of these volumes were also produced for libraries outside Tours. The earliest volumes to survive from the Tours scriptorium, produced from c. 730, were copied in order to supply the needs of a community of libraries. That sort of scriptorium was far more common than we have tended to realise, especially, if we have focused on twelfth-century scriptoria. Like the scriptorium of Luxeuil, which affirmed its monastic values through the extensive copying of works of spirituality both for individaul patrons and for religious foundations linked to that promient house, the scribes of Tours shared their resources by copying on commission. Their mass-produced gospel books, their Bibles and the anthology of texts which commemorate and celebrate the life and miracles of St. Martin, set Tours at the centre of a network of ecclesiastical spirituality. This was in marked contrast to most Carolingian scriptoria, which copied chiefly for their own libraries, occasionally duplicating a rare text or the work of a house author. . . .

"The evidence of the surviving complete Tours Bibles in Monza, Cologne, London and Paris suggests that a complete Bible consisted of some 450 leaves, measuring c. 480 x 375 mm, with 50-2 lines per page. To copy a Tours Bible required some 210-25 sheep, whose shaped skins measured around 525 x 760 mm. The dimension of Carolingian sheep and their price await study, but has been suggested that sheep this size required available pasture throughout the winter. The format of the Bible was a marked improvement on the 1,030 leaves of the Codex Amiatinus and the estimated 920 leaves of Ceolfrith's smaller pandect, or the 72-line format of the two-column eighth-century Spanish half-uncial Bible, León, Cathedral, MS 15. Though the size of the sheet was much larger, the number of leaves required to copy a Tours pandect was less than required to copy the multi-volume Bibles of Corbie, St Gall or Würzburg. But the saving in parchment depended on the excellence and the unformity of the scribes who copied the c. 85,000 lines of Alcuin's text."