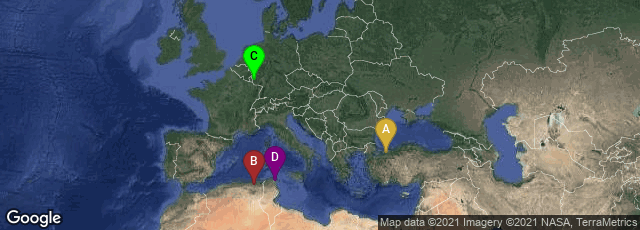

A: Kocaeli, Turkey, B: Constantine, Wilaya de Constantine, Algeria, C: Trier, Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany, D: Amilcar, Site archéologique de Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia

Remarkably little is known about the libraries of individuals in classical, Hellenistic, or even medieval times. In his small book, The Library of Lactantius (Oxford, 1978) R. M. Ogilvie studied the books that the Latin Christian apologist Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (Lactantius) read and knew well. Born in North Africa, possibly at Cirta in Numidia (modern Algeria), Lactantius, a professional rhetor, or teacher of rhetoric, was summoned to the Imperial Court at Nicomedia by the Roman emperor Diocletian. After converting to Christianity Lactantius resigned his post before the publication of Diocletian's first Edict Against the Christians (February 24, 303), and lived in poverty as a writer until he became advisor to the first Christian Roman emperor Contantine I, guiding Constantine's religious policy as it developed, and serving as tutor of Constantine's son Flavius Julius Crispus. It is believed that Lactantius may have followed Crispus to Trier when Crispus was made Caesar (lesser co-emperor) and sent to that city. The circumstances of Lactantius's death are unknown.

Lactantius's primary work, Divinae Institutiones (Divine Institutes), was an early systematic presentation of Christian thought. It was considered somewhat heretical after his death, but Renaissance humanists took a renewed interest in Lactantius, more for his elaborately rhetorical Latin style than for his theology. The early humanists called him Cicero Christianus (Christian Cicero), and his Opera (1465) was the first dated book printed in Italy.

The earliest surviving, and probably the most reliable text of Lactantius's Opera is Bologna, R. Biblioteca Universitaria 701, an uncial manuscript of 283 leaves written in North or Central Italy in a center of learning and fine calligraphy in the second half of the fifth century. Lowe, Codices Latini Antiquiores III (1938) No. 280. This manuscript is dated within little more than a century after Lactantius's death.

From Ogilvie's The Library of Lactantius, I quote Chapter XII, "Conclusion", pp. 109-10. The links are, of course, my additions:

"The library resources of Carthage or Alexandria or Rome were boundless but Lactantius was a traveller and could not rely on finding what he needed at Nicomedia or Trier. Nor, as we have seen, was he a scholar of great range and acumen: indeed his familiarity with Greek literature is slight, which may partly account for his evident unhappiness in Bithynia. The preceding chapters have attempted to discover what works he either used in writing. D. I. [Divinae Institutiones] or knew sufficiently well to be able to quote from memory.

"The resulting list is an interesting one. No Greek classical prose or poetry. His Greek reading is confined to oracular literature—Sibylline Oracles, oracles of Apollo and Hystaspes, some Orphic poems and some hermetic works—most of which may have been known to him through a single compilation on Theosophy. His Latin reading of poetry extends to Lucretius, Horace, Virgil, Ovid's Fasti and Metamorphoses, and Persius, Satires 2 and 6: for the rest he is indebted to one or more florilegia. Of classical prose authors Cicero leads the field, although the absence of so many speeches and other works, such as the De Finibus and the letters, is striking. He knew Livy's first Decade and Sallust's Catiline but not Tacitus nor, probably, Varro. He knew Seneca's philosophical works and an edition of Book I of Valerius Maximus. Aulus Gellius he came across after writing the D. I., but he may have had access to a similar compendium for some of his antiquarian and mythological material, unless it was all to be found in a commentary on the Aratea. An anthology provided him with most of his biblical and apocryphal quotations and, probably, with those apologetic commonplaces which he could not locate in Minucius, Cyprian, Theophilus, or Tertullian's Apologeticum.

"In his reading he offers an interesting comparison with Tertullian a hundred years before him, and Augustine or Jerome seventy years later. Terullian was writing during the great archaizing revival of the later second century, when old books were unearthed and reread, and before the political breakdown of the third century. he still knew Herodotus, Plato, Josephus, Pliny the younger, Tacitus, Juvenal, Ennius Varro, perhaps the elder Cato— to name but a few.

"In the later fourth century, pagans and Christians rediscovered some forgotten classics, especially Juvenal and Tacitus, but in the intervening period much literature had been lost beyond recall. Thus Jerome was familiar not only with the range of works which Lactantius knew but also with Plautus, Lucan and Martial. But in other respects he and Augustine are very similar to Lactantius. Augustine knew little Greek and derived his Platonic philosophy from Cicero (Epist. 118.2.10), whereas Jerome did not become closely acquainted with Greek literature until thirty years after his school days. On the other hand Virgil and Cicero's works, above all the Hortensius, meant much to Augustine (C.D. 1.3; Conf. 3.4.7). The same picture emerges from a study of Ausonius, or of Claudian although his interest and opportunities gave hima slightly wider range.

"Lactantius, therefore, in a real sense marks the beginning of the Middle Ages. Between the time of Tertullian and his own day the great process of survival had already jettisoned many literary treasures of Athens and Rome to oblivion."

As a small bibliophilic aside, I was surprised to acquire R. M. Oglivie's personal corrected copy of his book on Lactantius for only £26.